Atrioventricular Septal Defects Surgical Outcomes

Atrioventricular septal defects (AVSD), sometimes also called atrioventricular canal defects (AV canal), represent up to 5% of congenital heart defects. In a healthy heart, there are four chambers that contain blood with either less oxygen (the right-sided chambers) or more oxygen (the left-sided chambers) and are responsible for circulating blood to the rest of the body.

In a heart with an AVSD, there are abnormal holes in between the chambers of the heart. This allows blood with less oxygen to mix with blood that has more oxygen, preventing the heart from delivering as much oxygen to the rest of the body as it needs to.

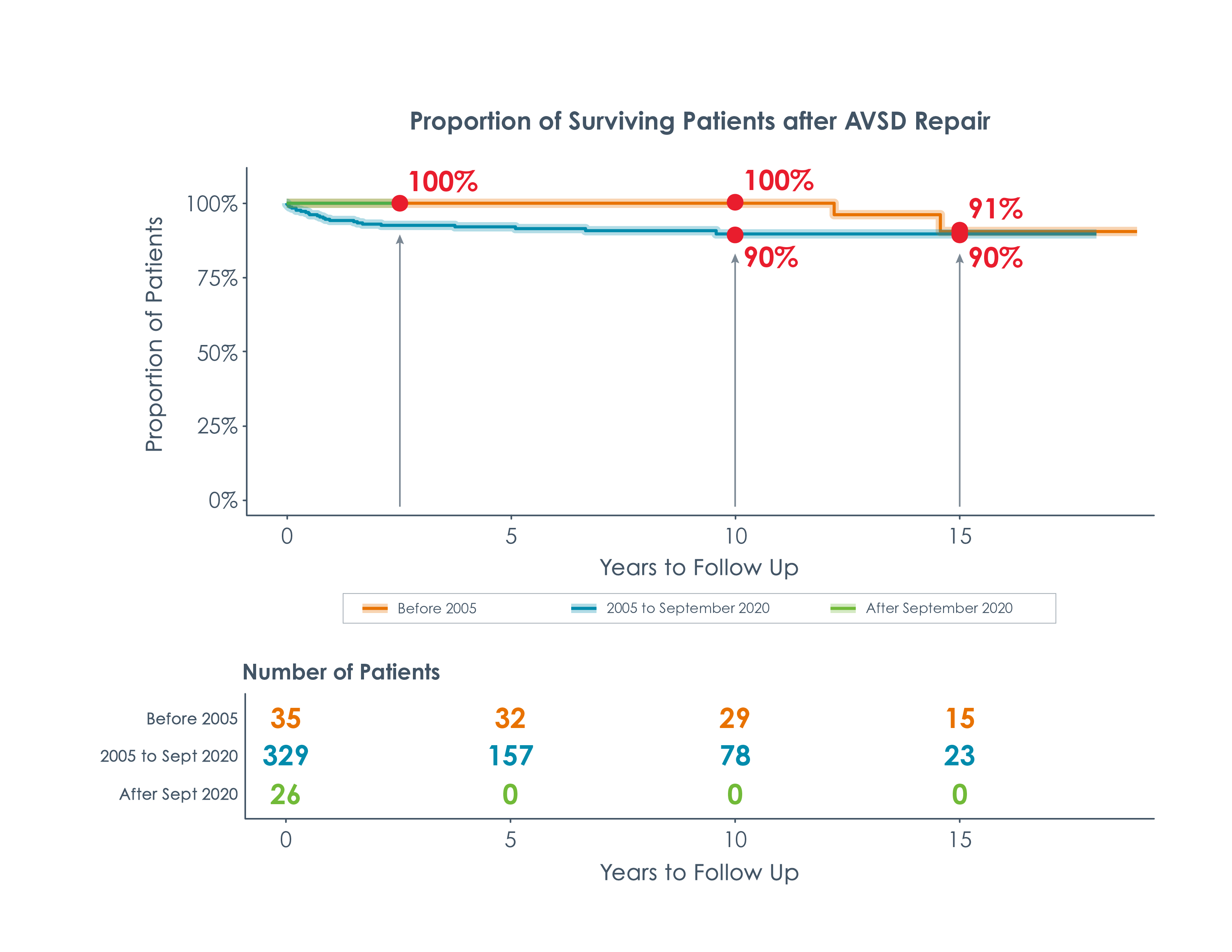

Long-Term Survival Outcomes After AVSD Surgery

This graph shows the likelihood that someone who received a repair for atrioventricular septal defect will survive over time. Each one of the three lines on the graph represents a different era at Children's National based on major changes to the makeup of the program or how patients are managed. The orange line is based on surgeries that took place before 2005, the blue is based on surgeries that took place between 2005 and September 2020, and the green line is based on surgeries that took place after September 2020.

The arrows at different points show:

- An estimated 100% of patients operated on before 2005 survived 10 years after their repair.

- An estimated 91% of patients who had repair surgery before 2005 survived 15 years after repair.

- An estimated 90% of patients who had their operation between 2005 and September 2020 will survive 10 years after repair.

- An estimated 90% of patients who had their repair between 2005 to September 2020 will survive 15 years after surgery.

- New surgical techniques implemented in 2020 are showing a 100% survival rate. It is too soon for long-term data on these techniques, but the early indicators are promising.

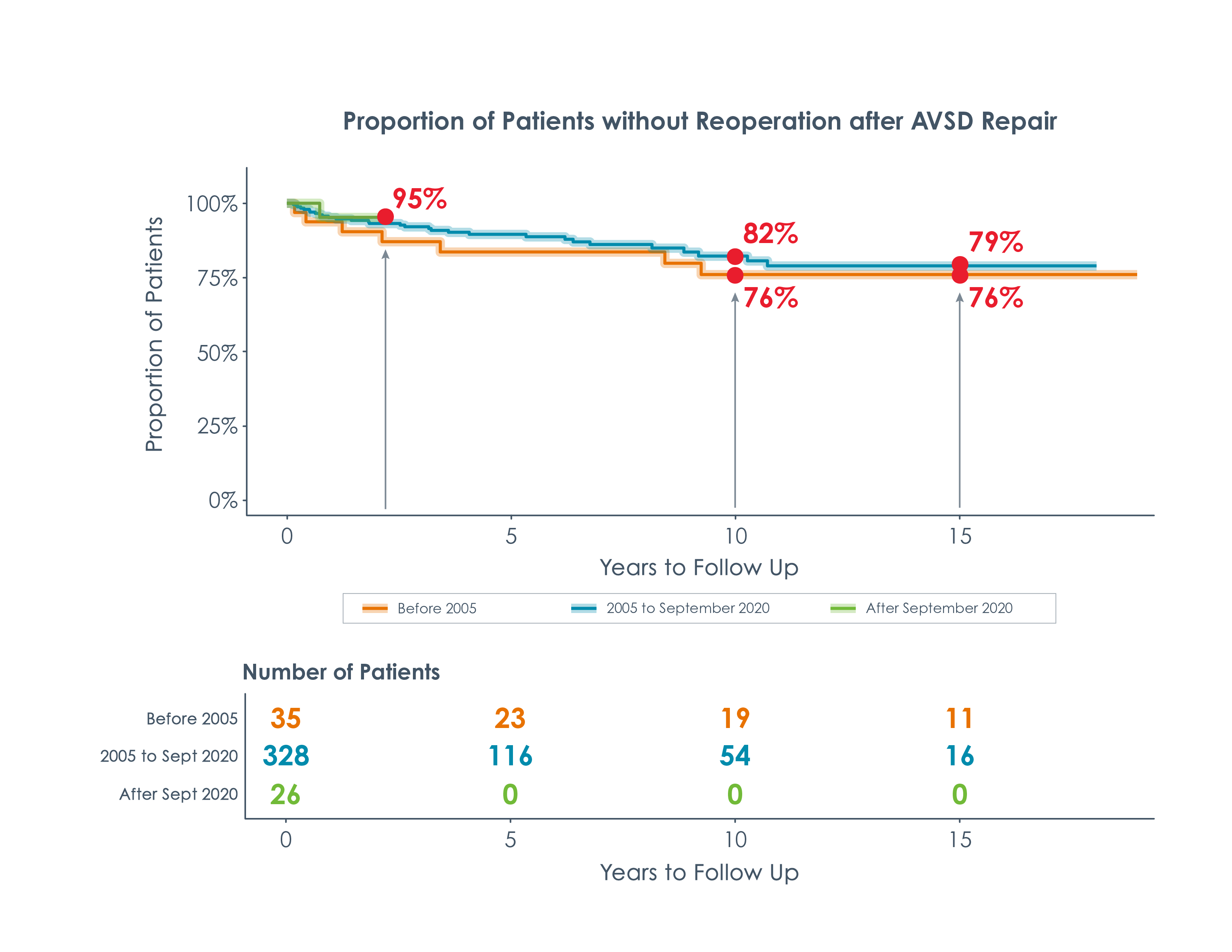

Risk of Reoperation for AVSD

This graph shows the risk that someone who received a repair for their atrioventricular septal defect will require another surgery (reoperation) over time. Each one of the three lines on the graph represents a different era at Children’s National based on major changes to the makeup of the program or how patients are managed. The orange line is based on surgeries that took place before 2005, the blue is based on surgeries that took place between 2005 and September 2020, and the green line is based on surgeries that took place after September 2020.

There is still a high likelihood that people who have surgery to repair AVSD will need some sort of reoperation later in life.

As shown in Figure 2, AVSD reoperations are often needed when:

- Problems arise over time in the valve that separates the receiving chamber and the pumping chamber on the left side of the heart (the left AV valve). This valve is supposed to prevent blood that the heart pumps out from flowing back into the collecting chamber, but over time the valve may deteriorate to the point where some blood leaks out to the collecting chamber anyway. This is called regurgitation.

- There are changes to the electrical system in the heart that control beating (arrhythmias) and blockages in the pathway leading from the left pumping chamber of the heart to the body (left ventricular outflow tract obstructions).

The arrows at different points of the graph in Figure 2 show:

- An estimated 76% of patients who had their operation before 2005 will not need a reoperation 10 years after their repair.

- An estimated 82% of patients who had their operation between 2005 and September 2020 will not need a reoperation 10 years after repair.

- Estimated rates of reoperation are fairly stable 15 years after surgery.

- Surgical techniques implemented in 2020 show early promise, with an estimated 95% of patients not needing a reoperation since repair, so far.

After an AVSD repair, the Cardiology team at Children's National will monitor the heart's form and function to make sure that, if such an operation is needed, it will be performed at the right time and with the best available technique.

How to Read and Interpret These Numbers

These graphs are called Kaplan Meier curves. They are produced using our own cardiac surgery data that is stored in the CNCORe database. The goal of these graphs is to predict what may happen 10 to 15 years after a child's initial heart surgery. We collect data and information for every single patient we have operated on. Over time, however, some people stop seeing their doctor or move to different states and countries—meaning that researchers do not have complete information for every patient across the years.

The CNCORe data is used to create graphs that estimate risk for something like reoperation using the data we do have, without needing every data point for every single patient.