Avery's Story

Twenty-nine-year-old Michelle Bullard was 40 weeks and three days pregnant and knew her first child could make her grand entrance any day.

As Michelle went into labor, her team at Virginia Hospital Center immediately knew something was wrong. Each time the woman experienced a labor pain, her baby’s heart rate plummeted. Her doctor said she would have to undergo surgery.

Just a few months earlier Michelle’s father, an otherwise healthy 57-year-old, did not survive open-heart surgery.

“When she said the baby is in distress, I heard ‘surgery’ and thought I may not make it. I was terrified,” Michelle says. After her daughter Avery was born but did not cry, that panic intensified. It went from slow motion to fast. People were asking me ‘Did you have complications during the pregnancy?’ All of a sudden, Avery was rushed to the Children’s National Health System neonatal intensive care unit. I caught a glimpse of her,” she says before her husband Benjy Bullard, 28 at the time, and Avery were whisked to Children’s National.

Faced with an APGAR score of one, which indicated the newborn was struggling, the team quickly recognized the infant had hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE), one of the most severe complications that can affect full-term infants. They told Benjy about whole-body therapeutic cooling that Children’s National was using to lessen the risk of long-term brain injuries among such vulnerable newborns. Full-term infants who undergo the therapy are wrapped in cooling blankets that temporarily lower their body temperature by about 3 degrees Celsius.

Reunited with her husband and infant at Children’s National, Michelle said she could feel the uncertainty. The mood was very solemn, yet the warm and caring clinical team counseled the family to give it a little more time.

“After that first 72 hours, everything began to look up,” Michelle says. “Avery turned it around: She went from being a very sick baby then, suddenly, the cooling treatment started to work. She started to react. She was starting to be taken off tubes. She went from being in a room full of machines to eventually being a little baby in a crib. It went from being a scary situation to a very hopeful situation.

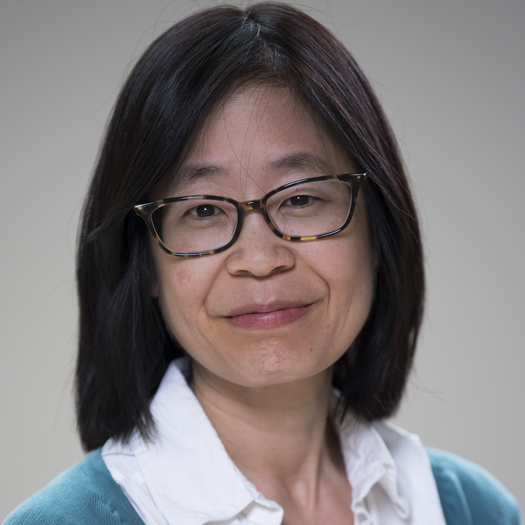

Even four years later, one memory stands out in especially sharp detail: Taeun Chang, M.D., director of Children’s Neonatal Neurology Program, gathered the care team and showed the family an image of Avery’s brain injury and explained what it could mean for her future.

“There were a lot of unknowns. We were told she probably will walk and talk─at some point in life. To me, that was a very scary thing to hear. We also were told her injury may be as minimal as having a learning disability once she entered elementary school,” the 34-year-old recalls. “Dr. Chang said when a newborn suffers a brain injury, that’s a horrible thing to hear. However, it’s like if you had a diary of an adult, and they had written on all the pages. Then, you rip out pages. You can’t replicate those missing pages. It’s harder to piece together where things are supposed to go. With a new baby, it’s like a blank diary missing a few pages. They’re able to work around it and create new stories.”

“Even now, I remember how dire Avery’s electroencephalogram (EEG) looked in the first 24 hours of life, as she began suffering a number of seizures immediately after birth,” Dr. Chang says. “Then, suddenly at 24 hours of life, Avery’s brain seemed to suddenly wake up, and her EEG improved markedly over the next 48 hours.

“And I also remember the love this little baby received from her family and their friends. It was a novel treat to hear singing in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). It made the entire NICU care team smile and Avery’s song became a celebratory one since it was evident by that point that this baby had taken a decided turn for the better.”

Avery, now age 4, continues to create new stories of her own.

“Dr. Chang says 60% of the families come out of therapeutic cooling with positive results; we’re part of that 60%,” Michelle says. “Avery had this injury but, as she developed, we realized her little body and her little brain worked around this injury.”

Avery’s development was supported by a multidisciplinary Children’s care team. That meant, as a late walker, Avery received physical therapy.

“All of a sudden, she was walking. Then, she was running. This little girl can run a mile in 13 minutes,” Michelle marvels.

In mid-October, the girl donned her Super Avery cape in bright pink─her favorite color─with a golden “A” emblazoned on the back to participate in Race for Every Child. Michelle pinned on a Super Avery logo as did Avery’s grandmother. A family friend hoisted a Super Avery poster in hot pink.

“She knows she’s a super star. We talk to her about her experience and how she’s special. She’ll tell me, ‘When I was little, the doctors had to take care of me. The doctors helped me get better,’” Michelle says.

It’s the same advice she would give to another family facing the same uncertain future.

“It’s OK to be scared. It’s OK to be worried. But have faith that your baby is going to be in the best hands possible with Children’s National and this team.”

Dr. Chang passed away in June 2022.